Curriculum Mapping Basics

Public and private learning organizations must continuously strive to ensure that their mission, vision, and goals are attainable and sustainable through designing and refining curriculum and instruction, which curriculum mapping embraces.

Education in the United States, as well as worldwide, is continuously in the midst of reform and new forms. There are, and will continue to be, requisites and recommendations annually based on such factors as national, state, and higher-ed standards; federal and state assessment accountability, including authentic applications with meaningful audiences; personalized learning; instruction that encourages diversity and student-centered learning; and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Curriculum Mapping Model

There are many research-based models designed to cultivate curriculum and instruction decision-making. Based on one or more models, a learning organization creates a framework model that necessitates educators and students be involved in the act of learning— students as learners; teachers as learners; teachers as designers of student learning, as well as personalized professional learning; and students as co-decision-makers with teachers about their learning.

The curriculum mapping model based on Dr. Heidi Hayes Jacobs’ work (1997, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010) synthesizes aspects of traditional and contemporary models that focus on recognizing and enhancing learning, assessing, and teaching. Dr. Jacobs embraced the earlier mapping work of Fenwick English by articulating types of curriculum maps, as well as the need for vertical and horizontal alignment, cyclic reviews, and ongoing curricular dialogues. Jacobs (2004) states that:

“curriculum maps have the potential to become the hub for making decisions about teaching and learning. Focusing the barrage of initiatives and demands on schools into a central database that can be accessed from anywhere through the Internet can provide relief…Mapping becomes an integrating force to address not only curriculum issues, but also programmatic ones.” (p.126).

Curriculum mapping emphasizes the collaboratively planned learning, as well as what takes place individually in classrooms and lecture halls. Curriculum maps are most often recorded as units of study. Depending on a school’s, district’s, or higher-ed program’s short- and long-range curriculum and instruction goals, mapping often begins with designing collaboratively planned curriculum at a district or program level (Essential Map) and then at the school-site level (Consensus Map). (Note: If a school is choosing to map that is not doing so as part of a larger organization, the school would begin with designing Consensus Maps). The design process is oftentimes followed by having each teacher or professor record what takes place personally concerning learning and teaching in a Projected/Diary Map, or by aligning or embedding Instructional Unit Plans and/or Lesson Plans within a map’s appropriate unit of study.

Hale (2008) emphasizes that “curriculum mapping is not a spectator sport. It demands teachers’ ongoing preparation and active participation. There must also be continual support from administrators who have a clear understanding and insight into the intricacies of the mapping process.” (p. xv)

Mapping is an ongoing process. As the moral of The Tortoise and the Hare conveys: start slow and purposeful to reach sustainability. Depending on the framework used, for example, Understanding by Design® (UbD), a curriculum map’s unit of study elements may be predetermined. If there is no one current framework established, the most common foundational elements include content, skills, and assessments aligned to standards. Initially, or during later requirements, unit elements such as transfer, big ideas/enduring understandings, essential questions, detailed assessments and evaluation processes, resources, and best-practice lesson plans and activities are included. To gain insights into gaps, absences, and redundancies in curriculum or instruction, it is important to take adequate time to both create quality maps and units of study, and reviewing them for multiple purposes.

Curriculum maps are never considered “done,” nor is having maps meant to be the ultimate goal of curriculum mapping. Maps are a by-product of collegial dialogue and decision-making. The term mapping is a verb. Mapping constitutes active engagement and collaborative participation in an organization’s on-going curriculum, assessment, and instruction decision-making. Education is not a static environment since learning, and learning about learning, is in perpetual motion.

Curriculum maps are never to be used for evaluation or punitive damage. Maps are designed to provide authentic evidence of what is planned, as well as what has happened, in a school, throughout a district, or in a higher-ed program. Encouraging educators to collaboratively revisit, review, and revisecurriculum maps, coupled with time set aside to analyze the results of student assessments and teaching practices, are at the heart of mapping. This mindset is necessary to move toward sustainability and have curriculum mapping become ubiquitous with curriculum and instruction practices that continually improve student-learning expectations and experiences.

Curriculum Mapping’s Three Cs

Curriculum Decision-Making — Educators need to work collaboratively to make informed curriculum and instructional decisions. Curriculum mapping has two guiding principles related to these actions:

-

- Educators must consider “the empty chair,” which represents all students in a given school, district, or higher-ed program. All concerns, comments, questions, and decisions are welcome as long as they are “in the students’ best interests” (Jacobs, 2004).

-

- If there are recommendations to stop, start, modify, or maintain curriculum or instruction based on what is in the students’ best interests, there needs to be quantitative or qualitative data to support the recommendations (Jacobs, 2010).

These principles are logical and well-founded. Some may consider them easy to adhere to, but oftentimes this proves difficult in practice when dealing with the human factor. Barth (2006) refers to the “…elephant in the room—the various forms of relationships among adults within the schoolhouse might be categorized in four ways: parallel play, adversarial relationships, congenial relationships, and collegial relationships” (p.10). Not surprising, the first three do not elicit collegial dialogue and decision-making. Barth contends that “…empowerment, recognition, satisfaction, and success in our work—all in scarce supply within our schools—will never stem from going it alone … success comes only from being an active participant within a masterful group—a group of colleagues” (p.13, italics added). Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to provide educators with ample professional learning and quality meeting time to build collaborative relationships and hone their skills and abilities to be curriculum designers and instructional leaders.

Curriculum Coherency — Curriculum‘s root meaning is a path taken in small steps, which is what curriculum mapping advocates. Curriculum mapping asks educators to record, implement, reflect on, and revise their curriculum and instruction. Unfortunately, even with the advent of Open Educational Resources (OER), many are still engaged in what Jacobs (2008) refers to as “treadmill teaching,” running breathless on grade-level, content-area, or program treadmills, desperately trying to get everything they perceive needs to be taught, taught. If teachers are provided with opportunities to slow down and collaboratively evaluate standards, learning expectations, habits, and soft skills across grade levels or courses to design learning expectations, curriculum coherency emerges, which benefits teachers, and most importantly, students. Teachers (and students) can work smarter, not harder, when selecting instructional resources and supports to aid their learning environments.

Curriculum Transparency Tool — Curriculum Maps (and related Instructional Unit Plans and Lesson Plans) are developed and maintained in an Internet-based mapping system that incorporates a systemic mindset: easy access to all grade levels and courses in one school, multiple schools, a district, or higher-ed program or programs. A mapping system serves as a 24/7 communication toolthat provides educators and administrators with evidence of the planned and taught curriculum and instruction—horizontally (same grade level or course) and vertically (series of grade levels or courses) for past, present, and future academic years. Multiple searching and reporting features, as well as internal communication capabilities, such as leaving notes and revision suggestions, allow educators and administrators to participate synchronously and asynchronously in the curriculum and instruction decision-making process. A mapping system’s ability to allow educators to collaboratively design maps’ units of study, instructional unit plans, and lesson plans, as well as upload resources and support materials, aids in supporting the ongoing mapping process.

Curriculum Mapping and Second-Order Change

Empowering teachers to be collaborative leaders in curriculum design and instruction is paramount and a top priority when introducing a curriculum mapping initiative. As mentioned by Hale (2008):

Curriculum mapping involves systemic, or second-order, change. Marzano, Waters, and McNulty (2005) state that “incremental [first-order] change fine tunes the system through a series of small steps that do not depart radically from the past. Deep [second-order] change alters the system in fundamental ways, offering a dramatic shift in direction and requiring new ways of thinking and acting” (p.66). Second-order change causes members of a learning organization to make a series of personal and collective mental model shifts.

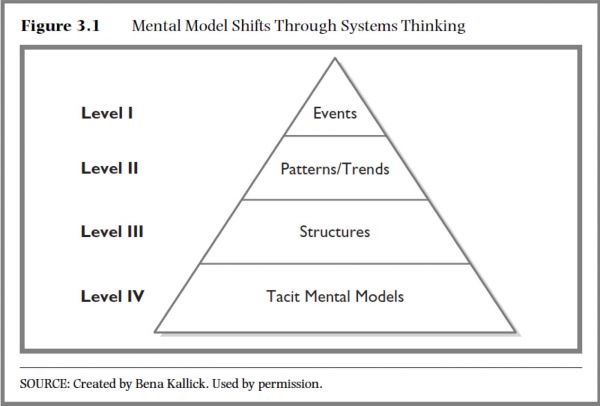

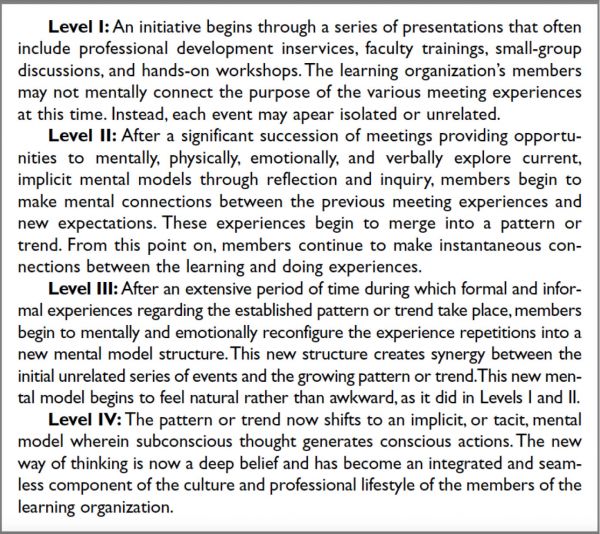

Kallick (2006) incorporates Senge, Cambron-McCabe, Lucas, Smith, and Kleiner’s (2000, pp. 80-83) Systems Thinking Model in her explanation of the mental shifts teachers and administrators make to internalize a new initiative. The series of shifts take approximately three years before reaching Level Four (Figure 3.1).

Administrators, as always, play a critical supportive role in a second-order change wherein educators are being asked to learn or expand their understanding of what it means to be curriculum designers and decision makers. Hale and Dunlap (2010) emphasize the need for administrators and key teachers to exhibit transformational leadership:

“A transformational leader encourages individual members of the group to participate in collaborative learning experiences and ongoing application, and allows each member of the group to have an equal voice, whether a member is sharing information or providing thoughts and opinions on the current status or future direction of an initiative. This encouragement is central to curriculum mapping. Transformational leadership embraces teaching, coaching, mentoring, facilitating, inspiring, influencing, and bringing about effective change.” (p. 16)

One must recognize that curriculum mapping is not an external program or best practice that “comes and then goes” in a few years. It is designed to become an omnipresent component of an educational system’s infrastructure. One district I worked with crafted a motto: Curriculum mapping is not one more thing on our plate—it is the plate! While this motto accurately describes mapping’s intent, the reality is that it will take time and energy (from personal experience, up to four or five years to reach Level IV’s subconscious thoughts generating conscious actions), as well as moments of frustration, for educators and administrators to embrace and naturally begin to apply the connectivity of curriculum mapping to all aspects of learning and teaching.

Your Curriculum Mapping Journey

Success is often based on improved student learning. While curriculum mapping does address this concern, it delves much deeper. It travels to the heart of our profession: caring about the journey a student takes upon entering Kindergarten, exiting as a high-school or upper-school graduate, enrolling in a higher-education learning environment, participating in the workforce, and becoming a fulfilled and contributing adult to spur on the next generation.

Please be advised: Curriculum mapping is not a quick fix. It has a learning-and-application curve, just as anything worthwhile pursuing does. For a time, you and your colleagues will be learners, since much of what is involved in designing curriculum, especially systemically, is not included at all or in-depth in an undergraduate (and most graduate) programs. All those involved must be provided adequate cognitive (and metacognitive) processing time to explore and understand how mapping fits in with what “we have been doing, as well as what needs to take place to advance our curriculum work.”

Some will learn faster than others, some will need more support, while some others may refuse to actively participate. It is important to allow for understanding and application in small steps. It is recommended that a leadership team consisting of educators and administrators be involved in a curriculum mapping initiative’s prologue, which includes time to: make sense of the concepts associated with mapping, analyze implementation needs based on the learning organization’s culture and climate, develop both short- and long-range goals, determine map unit template elements based on framework(s), and once implemented, celebrate both small and large milestones along the way.

Be ready and willing to learn as much as you can about curriculum mapping historically and currently by reading, attending conferences, taking courses, and networking. If you would like to network with me about your past, current, or future curriculum mapping journey, I would love to meet with you! Here are a few ways we can connect:

References

Barth, R. S. (2006). Improving relationships within the schoolhouse

Educational Leadership 63(6): 8–13.

Hale, J. A. (2008). A guide to curriculum mapping: Planning, implementing, and sustaining the process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hale, J. A. & Dunlap, R. E. (2010). An educational leader’s guide to curriculum mapping: Creating and sustaining collaborative cultures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Jacobs, H. H. (1997). Mapping the big picture: Integrating curriculum and assessment K-12. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jacobs, H .H. (2004). Getting results with curriculum mapping. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jacobs, H. H. (2006). Active literacy across the curriculum: Strategies for reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Larchmont, NY: Eye On Education.

Jacobs, H. H. (2008). Keynote presentation. Glendale, AZ: Regional Curriculum Mapping Conference.

Jacobs, H. H. (2010). Curriculum 21: Essential education for a changing world. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jacobs, H. H. & Johnson, A. J. (2009). The curriculum mapping planner: Templates, tools, and resources for effective professional development. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kallick, B. (2006). Sustaining the mapping initiative. Keynote presentation at Twelfth National Curriculum Mapping Institute, Santa Fe, NM.

Marzano, R., T. Waters, and B. McNulty. (2005). School leadership that works: From research to results. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Senge, P., N. Cambron-McCabe, T. Lucas, B. Smith, and A. Kleiner. (2000). Schools that learn: A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education. New York: Doubleday.

Contact Janet

Fill out the form below to contact Janet